Thursday, April 29, 2010

Five Best Plants to Attract Wildlife

Never thought of your garden as a wildlife preserve? Well, it may be time. The statistics about human impact on nature are grim. Consider a few: America grows by 8640 people per day, and we sprawl across an additional two million acres per year (the size of Yellowstone Park). The total paved surface of the country is the size of Missouri, and our non-paved surfaces are mostly lawn and sterile plantings. What's left of our woodlots and forests are invaded with 3400 species of alien plants like bittersweet, honeysuckle and privet that have consumed 100 million acres of land (the size of Texas). In the lower 48 states, humans have converted 54% of the total land into cities and suburbs, and 41% into various forms of agriculture. That's an astounding 95% of total land dedicated to man-made use.*

Nature no longer happens somewhere else. Gardeners represent the last best chance to reclaim some of our lost biodiversity. Our local animals need native plants--preferably lots of them in contiguous and connected areas--to survive and reproduce. While I love many Asian or European ornamentals, they support only a tiny fraction of the wildlife that natives do. For example, a Kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa) supports no insect herbivores while our native flowering dogwood (Cornus florida) supports 117 different species of moths and butterflies.

So what should you plant? Turns out, not all native species are equal. Some plants sustain much more diversity than others. University of Delaware professor Douglas Tallamy has studied eastern native plants and documented the different species they host. Check out this list of five SUPERPLANTS that support wildlife.

1. Oak Trees (Quercus)

Oak trees top the list for the total number of species they host. They support an astounding 534 species of butterflies and moths, nearly five time the amount of a Beech tree. In addition, their acorns provide an abundant food source for small mammals and birds. Oaks have been diminishing in forests as a result of fire suppression, all the more reason to add one to your yard. Plus, oaks are a beautiful and elegant, providing shade in the summer and allowing light in the winter (great for energy efficiency). Try an underused oak like the stunning Scarlet Oak (Quercus coccinea) for fall color, or the Nuttall Oak (Quercus nuttalli) for vigor and ease of transplant.

2. Goldenrods (Solidago)

Goldenrods support the highest number of moths and butterflies of any herbaceous species in the study, a whopping 115 different species. They are also an important nectar source for native bees and insect pollinators. Wait, don't Goldenrods cause hay fever? No. It gets blamed for it because it blooms at the same time as Ragweed. Most goldenrod species are drought tolerant, low maintenance, and have a long season of bloom. Try a Goldenrod cultivar like 'Fireworks' or 'Little Lemon' for a late summer show.

3. Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) image from mobot.org

Black cherries are rare in the nursery trade, mostly because they are considered a weed for so many years. But Black Cherries are among the most ecologically productive plants in the U.S., supporting an astounding 456 different species of moths and butterflies. This tree is a veritable food court for wildlife: their beautiful white blooms in April provide nectar for bees and other pollinating insects, their fruit provides food for birds and small mammals, and their trunks are favorite foraging ground for woodpeckers. Plant Black Cherries along the border of your property, preferably contiguous with other trees and shrubs to maximize the wildlife impact. If you can't find tree sizes in the nursery, don't fret. Plant denser groups of smaller saplings for a lush and informal hedge row. Here is a link where you can get seeds.

4. Asters

Asters are second only to Goldenrods in terms of the number of moths and butterflies they support (112 different species!). American asters are among the most colorful and showy of all native perennials. Don't even bother with Asian varieties; the American natives are every bit as intense, drought tolerant, and easy to grow. Plus, we are spoiled for choice. The New England Aster (Aster novae angliae) are great for massing, the Wood Asters (Aster divaricatus & cordifolius) are good in the shade, and Smooth Aster (Aster laevis) are great for interplanting among grasses. My personal favorite are the Aromatic Asters (Aster oblongifolius) like 'October Skies' (pictured) and 'Raydon's Favorite.' Compact (18-24"), vigorous, and an explosion of mid-autumn color.

5. Willows

One of the most under appreciated shrubs in America turns out to be one of the most ecologically beneficial ones. Willows form large shrubs or small trees that stabilize streambanks, remove pollution from water, and provide food for as many as 455 different moths and butterflies. Our colonial forbears used willows for baskets, building construction, and fencing, but we've all but forgotten this amazing shrub. It's not only practical, but beautiful. Bluestem Nursery is the authority on the many different uses and varieties of willows. Consider a willow for its steely blue leaf color, or for its outstanding stem color that rivals Red Stem Dogwoods. Bluestem Nursery has catalogued just a few of the many uses for these plants. They're incredibly fast growing, too. If you want an instant hedgerow, or a living fence (see picture) this is your plant.

(Statistics from Bringing Nature Home: How Native Plants Sustain Wildlife in Our Gardens by Douglas W. Tallamy.)

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

Botanicals for the Green Revolution: The Prints of Angie Lewin

Angie was not always strongly connected to the natural world. For years Angie lived in north London as an illustrator. When she and her husband decided to buy a holiday cottage on the coast road in Norfolk, everything changed. The clifftops and saltmarshes of the North Norfolk coast inspired Angie to return to print making, a discipline she had studied in graduate school. Angie had previously studied garden design in her thirties, but found it took the joy out of gardening. But it did open her eyes to plants. "I became fascinated by the structure of plants," says Angie, "especially those that were about to flower or had flowered already."

Her style is recognizable: the colors are a retro palette, and the arrangement is a mix of arts and crafts and mid-century modern. But her eye for horticultural detail elevates her designs. In her prints, you can feel the connection between plant and place, and its this element that makes her work strikingly original. You get a sense from her work that if you see the plant well enough, you will know the larger landscape. Though nature is abstracted, the ecology is still present. "I like looking at the landscape through the plants," Angie says.

Goatsbeard, dandelions, cow parsley, fennel, and sea lavender--Angie is able to turn gardener's weeds into expansive landscapes. The process is laborious and time-consuming. For each print, Angie begins by sketching. The sketches become detailed sketches, which then get cut into the wood. Each color necessitates a separate block, each of which takes up to a week to cut. If she makes a mistake while cutting, she has to start from the beginning. The final piece is printed on delicate Japanese paper, one block at a time. Since everything is done by hand, Angie only runs small prints. "I have so many sketches that I'm always keen to move on to the next print."

The end results have attracted attention. Angie's prints have donned the cover of garden writer Noel Kingsbury new book, Natural Garden Style. Kingsubry has long trumpeted the value of the structure of plant, not just its bloom or color, so her art was a good philosphic fit. In addition, Angie has completed covers for Leslie Geddes-Brown's Garden Wisdom and Jeremy Page's Salt. Author Leslie Geddes Brown explains, "The whole book was, in its turn, inspired by the art of Angie Levin, who brings her own vision of the natural world to her work."

To learn more about Angie Lewin's work, you can visit her website.

Sunday, April 25, 2010

Your Herbs are Trying to Kill You

The Dangerous and Seductive World of Phytochemicals

Among my many plant obsessions, growing and cooking with herbs and spices is one my favorite horticultural pastimes. Herbs are, after all, a bridge between two things I love: the garden and the kitchen. During this past winter, while confined to reading about gardening, my plant studies turned to ethnobotany, the study of the complex relationship of people and plants. What I read changed the way I look at those seemingly benign green lumps outside my kitchen.

“Plants are virtuosos of biochemical invention,” writes food science writer Harold McGee. The chemicals in plants are potent stuff. That boring potted oregano on your patio is actually an arsenal of phytochemicals. To chew on a raw leaf of oregano is not pleasant, and that’s mostly due to the toxicity of the chemicals in the plant. In fact, the purified essence of oregano and thyme can be bought from chemical supply companies with warning labels on them. Surprisingly, that’s exactly the plant’s goal. While animals can use their mobility to avoid predators, stationary plants resort to chemical warfare. Each plant produces thousands of strong, sometimes poisonous chemicals to ward off animals, humans, bacteria, and insects.

“Plants are virtuosos of biochemical invention,” writes food science writer Harold McGee. The chemicals in plants are potent stuff. That boring potted oregano on your patio is actually an arsenal of phytochemicals. To chew on a raw leaf of oregano is not pleasant, and that’s mostly due to the toxicity of the chemicals in the plant. In fact, the purified essence of oregano and thyme can be bought from chemical supply companies with warning labels on them. Surprisingly, that’s exactly the plant’s goal. While animals can use their mobility to avoid predators, stationary plants resort to chemical warfare. Each plant produces thousands of strong, sometimes poisonous chemicals to ward off animals, humans, bacteria, and insects. Herbs and spices stockpile aroma chemicals in oil-storage cells connected to glands on the surface of the leaves. Though we think of herbs or spices having a single flavor, they often contain a mixture of several aromatic compounds combined. So when you smell coriander seed, for example, you smell both flowery and lemony; bay leaves mix eucalyptus, pine, and flowery aromas. The individual flavor chemicals are a fascinating study unto themselves: cineole is found in sage, basil, and nutmeg and gives these plants their characteristic freshness; the phytochemical estragole gives tarragon its anise flavor; and safrole gives both the herb hoja santa and the root of the sassafras tree (from which root beer is derived) its distinctive “candy-shop” aroma.

The great irony is that humans have come to love these very plants that mean to do us harm. We have even learned to enjoy chemicals that are designed to hurt us. Think of the pungent sulfuric compounds of onions and the allium family, or the burn of capsicums from peppers. Ginger, mustard, horseradish, wasabi--we convert these weapons into pleasure through breeding and cooking. Cooking dilutes the effect of the essential oils. We still ingest these toxins, but at lower levels because they are mixed with other foods.

So are these phytochemicals bad for us? Probably not in small doses. In fact, most herbs and spices contain phenolic compounds that are chock full of antioxidants which prevent DNA damage, cancers, and inflammation. But certain people should be careful. Pregnant women, in particular, should be cautious about ingesting certain herbs or spices, as some are feared to induce contractions. Developing fetuses may not have developed the immunity to the toxins of certain phytochemicals. So check with your doctor.

Science seems to confirm what our ancestors knew for centuries: that herbs and spices are seductive, yet powerful alchemists. I will never look at my potted oregano the same way again.

Friday, April 23, 2010

New Planting Aimed at Restoring the American Chestnut Tree

Restoring the Majestic Chestnuts to Appalachia

Once the king of the eastern forests, the American Chestnut tree was devastated by blight early in the twentieth century. The blight was a result of importing Asian chestnut species to America. The native trees had no immunity to the foreign blight. Now the only chestnuts that remain in the wild are small seedlings that die when they reach a certain size.

The Nature Conservancy has teamed with the American Chestnut Foundation to plant over 1,000 acres of land in Nelson County, Viriginia, with a new chestnut variety that may resist the blight. While the new cultivar has been hybridized with the blight resistant Chinese species, the genetic makeup of the trees is still 95% American in their makeup.

See more about the planting here.

Once the king of the eastern forests, the American Chestnut tree was devastated by blight early in the twentieth century. The blight was a result of importing Asian chestnut species to America. The native trees had no immunity to the foreign blight. Now the only chestnuts that remain in the wild are small seedlings that die when they reach a certain size.

The Nature Conservancy has teamed with the American Chestnut Foundation to plant over 1,000 acres of land in Nelson County, Viriginia, with a new chestnut variety that may resist the blight. While the new cultivar has been hybridized with the blight resistant Chinese species, the genetic makeup of the trees is still 95% American in their makeup.

See more about the planting here.

Thursday, April 22, 2010

Loosen Up that Landscape!

An Earth Day Challenge to Gardeners and Designers

"Do gardens have to be so tame, so harnessed, so unfree? What's new about our New American Garden is what's new about America itself: it is vigorous and audacious, and it vividly blends the natural and the cultivated." James van Sweden

My former boss and mentor, James van Sweden was always quotably evangelistic about the need for American gardens to loosen up. Founder of the New American Garden style, James van Sweden and Wolfgang Oehme created a legacy of projects that presented a beautiful and lush alternative to the typical American garden scene: a sea of lawn with overgrown evergreens stuffed under foundations.

James van Sweden is hardly the first or only voice advocating for an alternative to the typical American yard. Organizations like Lawn Reform, writers like Rick Darke, and landscape architecture firms like Andropogon have all offered compelling alternatives to the typical American landscape. But forty years after the first Earth Day, I have to ask: has the American garden style really progressed?

Instead, let me present a case for a radically different landscape, a departure from the traditional obsession with fixed forms. My humble advice to gardeners and designers for Earth Day is:

4. Bulk up that Biomass, especially for Pollinators: The amount of native biomass (the total mass of living matter in an area) is in severe decline thanks to development. But gardens represent one of the best opportunities to reclaim it. Carve out areas dedicated to wildness in your yard. Plant your borders with a loose mix of native shrubs; allow part of your lawn to convert to meadow; or let that low area become a rain garden or biofiltration zone. University of Delware professor Doug Tallamy has proven that native plants support an exponential number of more pollinators than do exotic plants. Plants that support butterflies, bees, and other insects invite birds and other wildlife into the garden. Check out Doug’s list of the most effective plants for Lepidoptera.

4. Bulk up that Biomass, especially for Pollinators: The amount of native biomass (the total mass of living matter in an area) is in severe decline thanks to development. But gardens represent one of the best opportunities to reclaim it. Carve out areas dedicated to wildness in your yard. Plant your borders with a loose mix of native shrubs; allow part of your lawn to convert to meadow; or let that low area become a rain garden or biofiltration zone. University of Delware professor Doug Tallamy has proven that native plants support an exponential number of more pollinators than do exotic plants. Plants that support butterflies, bees, and other insects invite birds and other wildlife into the garden. Check out Doug’s list of the most effective plants for Lepidoptera.

5. Have fun: One of the first reactions I get when I tell people I’m a landscape architect is an immediate moan about how terrible their yard is. People don’t know what to do and are overwhelmed by the maintenance required of mowing lawn and clipping shrubs. While I believe in principles of design, and in the need for landscape professionals, I believe more strongly in people having a joyous engagement with their garden. No matter what that looks like. So get out there, start with a manageable project, and create the change that loosens up your yard. Be daring, be bold, and have some fun, for crying out loud.

"Do gardens have to be so tame, so harnessed, so unfree? What's new about our New American Garden is what's new about America itself: it is vigorous and audacious, and it vividly blends the natural and the cultivated." James van Sweden

My former boss and mentor, James van Sweden was always quotably evangelistic about the need for American gardens to loosen up. Founder of the New American Garden style, James van Sweden and Wolfgang Oehme created a legacy of projects that presented a beautiful and lush alternative to the typical American garden scene: a sea of lawn with overgrown evergreens stuffed under foundations.

James van Sweden is hardly the first or only voice advocating for an alternative to the typical American yard. Organizations like Lawn Reform, writers like Rick Darke, and landscape architecture firms like Andropogon have all offered compelling alternatives to the typical American landscape. But forty years after the first Earth Day, I have to ask: has the American garden style really progressed?

For home gardens, there are small signs of progress. In the last two years, there has been an increase in vegetable gardening, a renewed interest in native plants, and the occasional person getting rid of their lawn. Despite these glimmers of hope, there is little indication that the style of gardening has actually changed. The basic ratio of lawn (~90%) to planting bed (~10%) remains the same. And what makes up the paltry planting beds are mostly stiff evergreens.

What’s worse is how many professional landscape architects or garden designers still perpetuate stiff and formulaic designs. In the name of modernism, how many urban plazas or institutional sites arrange evergreens in rigid stripes? Or how many self-trained garden designers fill backyards with uber-wavy lawns (because curves are natural!) only to dot in twelve perennials and four shrubs?

1. Invert the Relationship of Lawn to Planting Bed: Think of your lawn as an area rug, not as wall to wall carpeting. Lawns are best when they are defined on all sides by hardscape or planting beds. This gives them legibility and definition and gives you an opportunity to show off loose perennials, grasses, and shrubs around it. If you’re lawn is more than 50% of your yard, it’s probably too big.

2. Use a Majority of Plants that Change Seasonally: There’s nothing more satisfying in gardening than watching a landscape change through the seasons. Watching plants emerge out of the ground in spring, fill up in volume and color in summer, and then dry in winter connects you with the cycles of the seasons. Dedicate a large percentage of your yard (at least 1/3) to perennials, grasses, and deciduous shrubs—mostly native—and enjoy the drama of the seasons.

3. Think Winter Interest, not Just Evergreens: While every garden or landscape needs some evergreens, most American landscapes use far too many. Most ornamental and native grasses dry beautifully in the winter, and many perennials yield stately seedheads that look stunning in the snow. Include native deciduous shrubs like Itea virginica, Cornus alba, or Ilex verticillata for colorful stems and berries in the winter.

4. Bulk up that Biomass, especially for Pollinators: The amount of native biomass (the total mass of living matter in an area) is in severe decline thanks to development. But gardens represent one of the best opportunities to reclaim it. Carve out areas dedicated to wildness in your yard. Plant your borders with a loose mix of native shrubs; allow part of your lawn to convert to meadow; or let that low area become a rain garden or biofiltration zone. University of Delware professor Doug Tallamy has proven that native plants support an exponential number of more pollinators than do exotic plants. Plants that support butterflies, bees, and other insects invite birds and other wildlife into the garden. Check out Doug’s list of the most effective plants for Lepidoptera.

4. Bulk up that Biomass, especially for Pollinators: The amount of native biomass (the total mass of living matter in an area) is in severe decline thanks to development. But gardens represent one of the best opportunities to reclaim it. Carve out areas dedicated to wildness in your yard. Plant your borders with a loose mix of native shrubs; allow part of your lawn to convert to meadow; or let that low area become a rain garden or biofiltration zone. University of Delware professor Doug Tallamy has proven that native plants support an exponential number of more pollinators than do exotic plants. Plants that support butterflies, bees, and other insects invite birds and other wildlife into the garden. Check out Doug’s list of the most effective plants for Lepidoptera. 5. Have fun: One of the first reactions I get when I tell people I’m a landscape architect is an immediate moan about how terrible their yard is. People don’t know what to do and are overwhelmed by the maintenance required of mowing lawn and clipping shrubs. While I believe in principles of design, and in the need for landscape professionals, I believe more strongly in people having a joyous engagement with their garden. No matter what that looks like. So get out there, start with a manageable project, and create the change that loosens up your yard. Be daring, be bold, and have some fun, for crying out loud.

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

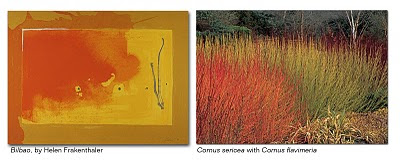

Abstract Expressionism and Planting Design: A Visual Analogy

I have always been drawn to abstract expressionism, both artistically and philosophically. Art critic Harold Rosenburg described the genre in terms of its action, "At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event." In the same way, I am drawn to planting design which is muscular and gestural. It speaks to the viewer at an emotional and spiritual level, and arranges plants in an ecologically sympathetic geometry. Here, I've set Joan Mitchell's After April is set next to a Piet Oudolf composition:

So in looking at the paintings I love, it becomes increasingly clear: the only planting worth doing is big, bold, and gestural. Strive for expansive, moody, luminous design. And remember that best naturalist design is first humanist.

And it is not just the bold use of color that makes this analogy; it is the philosophic stance of the artists that resonates with me. Painter Barnett Newman described the drive to paint, "What is the explanation of the seemingly insane drive of man to be painter and poet if it is not an act of defiance against man's fall and an assertion that he return to the Garden of Eden? For the artists are the first men." Likewise, if the design of landscapes is not fundamentally a humanistic endeavor, then it fails. Naturalistic design is not about imitating nature, it is an interpretation of nature that expresses the human condition. Both the painter and the architect create space for dwelling. Here Newman's painting declares space in the same way the birch grove does:

What was liberating about this style of painting was that in communicating a pure emotion, in expressing space, or in holding a void, the painting was liberated from the canvas. Great planting design likewise liberates a space from the confines of the site or property line. It gives the site a feeling of expansiveness by recalling a larger moment of nature. Or better yet, it arouses a longing for nature that is embedded in each of us.

Helen Frankenthaler once said, "A really good picture looks as if it's happened at once. It's an immediate image. For my own work, when a picture looks labored and overworked, and you can read in it. And I usually throw these out, though I think very often it takes ten of those over-labored efforts to produce one really beautiful wrist motion that is synchronized with your head and heart, and you have it, and therefore it looks as if it were born in a minute."So in looking at the paintings I love, it becomes increasingly clear: the only planting worth doing is big, bold, and gestural. Strive for expansive, moody, luminous design. And remember that best naturalist design is first humanist.

Sunday, April 18, 2010

The Urban Wilderness: The Poetics of Industrial Ruins and Untamed Nature

The Schoneberger Sudgelande Nature Park in Germany

Parks in America are the latest casualty to interest-group politics. The park designer must not only satisfy its municipal client, but must carefully redistrict the space to meet the demands of citizen advocates: the dog park people, the kiddie playground mommies, the bikers, the rollerbladers, the garden clubs, and the birders. Like a diplomat in the Balkans, the designer’s role is to gerrymander a site, parceling off piece by piece to the urban consumers. Parks today have more in common with theme parks—a ride for every user—than their pastoral predecessors.

The Schoneberger Sudgelande Nature Park is the perfect antidote to interest-group parks. Located just south of Berlin, Sudgelande is the site of a former railway switchyard. Abandoned after World War II, the site sat fallow for the past fifty years. During that time, a richly-diverse grassland and forest crept over the site, covering the industrial site in a green patina.

The park’s dystopian beauty engages the imagination in a way that most “designed” spaces fail to do. The ruins of the industry and technology are a profound expression of transitoriness, an intimation of mortality that is at once haunting and uplifting. Like Wordsworth at Tintern Abbey, the ruins of Sudgelande present the visitor with an ontological gap that stimulate the imagination rather than constrain it.

I love this park precisely because I believe in mystery. The way a rail track appears in a forest only to disappear into the brambles. Or how a tower emerges out of the canopy only to be eclipsed in vegetation. Mystery speaks to our souls before our intellect comprehends. Mystery has the power to radically de-center us, to pull us out of ourselves and ground us in a deeper reality.

My good friend, mentor, and visionary landscape architect, Ching-Fang Chen, first brought my attention to this park after she visited it in 2007. Fortunately for those of us in the Washington, D.C. area, Ching-Fang now works with Montgomery County (M-NCPPC) and is promoting sustainable park development based on the concept of managed succession and spontaneous vegetation.

Sudgelande offers a model for the future: a park that allows the layers of history to coexist with the spontaneous movement of nature. At the intersection of culture and wilderness, we behold mystery.

Parks in America are the latest casualty to interest-group politics. The park designer must not only satisfy its municipal client, but must carefully redistrict the space to meet the demands of citizen advocates: the dog park people, the kiddie playground mommies, the bikers, the rollerbladers, the garden clubs, and the birders. Like a diplomat in the Balkans, the designer’s role is to gerrymander a site, parceling off piece by piece to the urban consumers. Parks today have more in common with theme parks—a ride for every user—than their pastoral predecessors.

Thanks to the foresight of a local citizens group with the financial backing of an environmental alliance, this wild space was preserved and turned into a park. The former repair shop for locomotives was turned into a hall for artists and performers. The tangle of rail tracks move through forest and meadow, hinting at a structure that is dissolved by the wildness.

The park’s dystopian beauty engages the imagination in a way that most “designed” spaces fail to do. The ruins of the industry and technology are a profound expression of transitoriness, an intimation of mortality that is at once haunting and uplifting. Like Wordsworth at Tintern Abbey, the ruins of Sudgelande present the visitor with an ontological gap that stimulate the imagination rather than constrain it.

I love this park precisely because I believe in mystery. The way a rail track appears in a forest only to disappear into the brambles. Or how a tower emerges out of the canopy only to be eclipsed in vegetation. Mystery speaks to our souls before our intellect comprehends. Mystery has the power to radically de-center us, to pull us out of ourselves and ground us in a deeper reality.

My good friend, mentor, and visionary landscape architect, Ching-Fang Chen, first brought my attention to this park after she visited it in 2007. Fortunately for those of us in the Washington, D.C. area, Ching-Fang now works with Montgomery County (M-NCPPC) and is promoting sustainable park development based on the concept of managed succession and spontaneous vegetation.

Sudgelande offers a model for the future: a park that allows the layers of history to coexist with the spontaneous movement of nature. At the intersection of culture and wilderness, we behold mystery.

Saturday, April 17, 2010

The Most Important Urban Square You’ve Never Heard Of

Why Rotterdam’s Theater Square Represents a Turning Point for Urban Design

Art history rarely recognizes a masterpiece in its time. And neither does urban design and landscape architecture. So it’s time to pay homage to a groundbreaking urban square that changed the way designers approach urban sites.

Situated in the heart of Rotterdam, Schouwburgplein, or Theater Square was built in what was formerly a large blank space without character. Surrounded by nondescript lowrise towers that were built after the Nazi destruction, Schouwburgplein is built on top of underground parking. Designed by the landscape architecture firm West 8, the square is an interactive urban space, flexible and adaptive to the user’s needs.

In the tradition of Italy’s medieval squares, the design for Schouwburgplein emphasizes the importance of void, creating a panorama which opens to the skyline. The entire concept of the design revolves around the idea of adaptability. Lead designer Adriaan Geuze prefers the “emptiness” to overprogrammed urban spaces and argues that urban dwellers are capable of creating their own meaning in environments.

While traditional European squares are a representation of civic and religious power, Schouwburgplein empowers the public to determine their uses. Though the square is mostly flat and open, the secret to its effectiveness is the design of the urban surface. To emphasize the square as a stage, the entire surface is raised above the surrounding streets. In addition, the square’s mosaic of surface materials encourage different uses. The west side of the square is a poured epoxy floor containing silver leaves. The east side (with more sunlight) has a wooden bench over the entire length and warm materials including rubber and timber decking on the ground plane. The change in materials inspire different uses: children play a game on one surface, while skateboarders ride on another.

The surface of the square is embedded with connections for electricity and water, as well as facilities to build tents and fencing for temporary events. As a result, the surface is active and dynamic, a living field that allows the square to change day by day, hour by hour. This idea of urban surface as a living agricultural field is a departure from the philosophies of both classical and modern design. The urban surface is no longer a realm of fixed objects, but a living connective tissue capable of supporting indeterminate uses.

Like all good stage design, lighting is everything. The crane lighting designed for this project may be the most iconic element of the design. Coin-operated handles allow users to determine the height and placement of the lights. During the day, the shadow of the four crane lights move across the square like a clock, perhaps a reference to the Campo in Siena. At night, the dramatic lighting narrows the scale of the space as it casts a playful and theatric mood across the square.

Like all good stage design, lighting is everything. The crane lighting designed for this project may be the most iconic element of the design. Coin-operated handles allow users to determine the height and placement of the lights. During the day, the shadow of the four crane lights move across the square like a clock, perhaps a reference to the Campo in Siena. At night, the dramatic lighting narrows the scale of the space as it casts a playful and theatric mood across the square.

Good design has alway prompted contempt from institutions dedicated to neo-traditional. The nonprofit Project for Public Spaces has added Schouwburgplein to its Hall of Shame, claiming that “this is a perfect example of how a design statement cannot be a great square.” The site goes on to say the square is often underused during certain times of day, a clear indication of its failure. PPS unfairly blames the design of the square for problems of the fragmented and under-utilized urban context. Of course, the PPS has always been a bit critical of anything built after the Victorian era.

History remembers projects that mark a turning point. The design of Theater Square represents a shift from the square as fixed object to the square as dynamic field; from a site of representation and power to a site of democracy and openness; from overprogrammed public space to an enabling territory. The shift in thinking represented in this design is already percolating through universities and cutting edge design firms.

Art history rarely recognizes a masterpiece in its time. And neither does urban design and landscape architecture. So it’s time to pay homage to a groundbreaking urban square that changed the way designers approach urban sites.

Situated in the heart of Rotterdam, Schouwburgplein, or Theater Square was built in what was formerly a large blank space without character. Surrounded by nondescript lowrise towers that were built after the Nazi destruction, Schouwburgplein is built on top of underground parking. Designed by the landscape architecture firm West 8, the square is an interactive urban space, flexible and adaptive to the user’s needs.

In the tradition of Italy’s medieval squares, the design for Schouwburgplein emphasizes the importance of void, creating a panorama which opens to the skyline. The entire concept of the design revolves around the idea of adaptability. Lead designer Adriaan Geuze prefers the “emptiness” to overprogrammed urban spaces and argues that urban dwellers are capable of creating their own meaning in environments.

While traditional European squares are a representation of civic and religious power, Schouwburgplein empowers the public to determine their uses. Though the square is mostly flat and open, the secret to its effectiveness is the design of the urban surface. To emphasize the square as a stage, the entire surface is raised above the surrounding streets. In addition, the square’s mosaic of surface materials encourage different uses. The west side of the square is a poured epoxy floor containing silver leaves. The east side (with more sunlight) has a wooden bench over the entire length and warm materials including rubber and timber decking on the ground plane. The change in materials inspire different uses: children play a game on one surface, while skateboarders ride on another.

The surface of the square is embedded with connections for electricity and water, as well as facilities to build tents and fencing for temporary events. As a result, the surface is active and dynamic, a living field that allows the square to change day by day, hour by hour. This idea of urban surface as a living agricultural field is a departure from the philosophies of both classical and modern design. The urban surface is no longer a realm of fixed objects, but a living connective tissue capable of supporting indeterminate uses.

Like all good stage design, lighting is everything. The crane lighting designed for this project may be the most iconic element of the design. Coin-operated handles allow users to determine the height and placement of the lights. During the day, the shadow of the four crane lights move across the square like a clock, perhaps a reference to the Campo in Siena. At night, the dramatic lighting narrows the scale of the space as it casts a playful and theatric mood across the square.

Like all good stage design, lighting is everything. The crane lighting designed for this project may be the most iconic element of the design. Coin-operated handles allow users to determine the height and placement of the lights. During the day, the shadow of the four crane lights move across the square like a clock, perhaps a reference to the Campo in Siena. At night, the dramatic lighting narrows the scale of the space as it casts a playful and theatric mood across the square.History remembers projects that mark a turning point. The design of Theater Square represents a shift from the square as fixed object to the square as dynamic field; from a site of representation and power to a site of democracy and openness; from overprogrammed public space to an enabling territory. The shift in thinking represented in this design is already percolating through universities and cutting edge design firms.

Thursday, April 15, 2010

Governor's Island Park will be Developed by New York City.

"Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, Governor David A. Paterson, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and State Senator Daniel L. Squadron today announced an agreement on the long-term development, funding and governance of Governors Island in which New York City will have primary responsibility to develop and operate the island.

As a part of the announcement the City and the State together released the Governors Island Park and Public Space Master Plan, a comprehensive design for 87 acres of open green space, rejuvenating existing landscapes in the National Historic District, transforming the southern half of the island and creating a 2.2 mile Great Promenade along the waterfront."

See the design by landscape architecture firm, West 8 in this great interactive website:

http://www.govislandpark.com/

All images by (Rendering by West 8 / Rogers Marvel Architects / Diller Scofidio + Renfro / Mathews Nielsen / Urban Design +)

As a part of the announcement the City and the State together released the Governors Island Park and Public Space Master Plan, a comprehensive design for 87 acres of open green space, rejuvenating existing landscapes in the National Historic District, transforming the southern half of the island and creating a 2.2 mile Great Promenade along the waterfront."

See the design by landscape architecture firm, West 8 in this great interactive website:

http://www.govislandpark.com/

All images by (Rendering by West 8 / Rogers Marvel Architects / Diller Scofidio + Renfro / Mathews Nielsen / Urban Design +)

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Seeds of Change: How to get Tasty Veggies, Preserve Biodiversity, and Sock it to the Man

For the last two years, seed sales have hit record highs due in large part to the recession, the long winter, and a general increase in home gardening. The internet has made access to seeds cheap, easy, and fast. But how do you know which seed companies to buy from? And what are the environmental implications of your seed selection?

Want to know how to sock it to the agricultural conglomerates? Or how to save seeds from the fate of biotech companies and patent lawyers? Here’s a quick guide that explains what you should look for when buying seeds.

1. Support Small, Established Family-Owned Seed Distributors

Last year rumors spread across the internet that mega-seed company Burpee was bought by Monsanto, a massive agricultural conglomerate know for their genetically modified seeds. This rumor was not exactly true, as Monsanto actually acquired Seminis, a company that sells seeds to Burpee. Seminis sells not only to Burpee, but also to other large seed companies like Jung Seed, Johnny’s Selected Seeds, and Park seed. The big boys are indeed getting bigger.

While the ownership hierarchy and propagation ethics of large seed companies are murky, there are plenty of small, family-owned seed companies that offer a diverse selection. Select companies such as family-owned Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. This husband and wife team are taking on corporate agriculture with their grassroots “Pure Food” movement. Their charming populism is even more seductive when combined with pictures of their adorable daughter holding baskets of heirloom fruit. Just try and resist their free catalogue—it’s pure garden porn. In addition to Baker Creek, I’ve listed a few other notable seed companies at the bottom of this blog that are worth looking into.

2. Buy Open-Pollinated Seeds

Open pollination is the oldest method of developing seeds, predating agriculture itself. Open pollination means seeds either pollinate themselves (self-pollinating) or are pollinated by insects or bees. Why does this matter? Open pollinated seeds are dynamic, that is they change and adapt to local sites. The plant’s genetic material is often crossed with the genetic material of another plant of the same species, resulting in hardier strains adapted to the local microclimate. The great diversity of heirloom apples that once populated colonial America was a result of new strains of apples that were open pollinated. Supporting open pollination means you are creating more genetic diversity in our food and plant supply.

Most seeds on the market are hybrid seeds. These are the offspring of two distant and distinct parental lines. ‘Better Boy’ and ‘Early Girl’ tomatoes, for example, are hybrids of a couple different lines of the same species. The problem with hybrids is that breeders limit the genetic diversity to guarantee a certain trait—say size or a color. Even more insidious than hybrids are GMOs or genetically modified organisms. Much of mass food production—like the Idaho potato—are now propagated with GMO. This means a plant of one species has its genetic material spliced with plants of another species. These are crosses that would have never happened in nature. Eighty percent of all corn, ninety percent of all soybean, and almost ninety percent of all cotton comes from genetically modified plants. While the jury is out on whether GMO are actually harmful to us or the environment, one thing is for sure: the world food supply is genetically narrower than at any point in history. Using open pollinated seeds preserves genetic diversity.

3. Collect Your Own Seed; Trade with Others

Nothing makes you feel more grounded with the cycles of nature than harvesting, drying, and storing your own seeds. Want to connect on a spiritual level with the botanical universe? Or achieve gardening self-actualization? Collect seeds. Seed collection requires you to watch the reproductive cycle of plants, to notice pollination, and understand how and when flowers turn to seedheads. Plants will no longer be your blooming indentured servants, but free ecological beings capable of self-seeding and adapting.

Nothing makes you feel more grounded with the cycles of nature than harvesting, drying, and storing your own seeds. Want to connect on a spiritual level with the botanical universe? Or achieve gardening self-actualization? Collect seeds. Seed collection requires you to watch the reproductive cycle of plants, to notice pollination, and understand how and when flowers turn to seedheads. Plants will no longer be your blooming indentured servants, but free ecological beings capable of self-seeding and adapting. Last year, I noticed a Heuchera cultivar of mine had self-seeded in the garden. It was remarkable to notice the slight variations this new plant had from its parent, a result of the miracle of open pollination. My very own cultivar. Collecting seeds can be easy or difficult depending on the species. Start with annuals, then progress to perennials and shrubs.

Once you’ve achieved a small level of proficiency with seed collecting, you’re ready to embark on the next frontier: the black market seed trade. Ok, so maybe it’s not a “black” market, but there’s something downright exhilarating about arranging a backroom trade on the internet, then getting a shipment in a blank envelope. GardenWeb offers an a great starting place for seed exchanges. Become a bartering expert. Where your obsession takes you from there is up to you.

Check out these Family Owned Seed Companies:

www.sustainableseedco.com/pages/ A California company that sells untreated, open pollinated, heirloom seeds.

www.mariseeds.com/ A Tennessee company selling over 500 varieties of tomatoes and peppers. The Italian love oozes from this site.

http://www.rareseeds.com/ The Baker Creek Seed Company mentioned above.

www.dianeseeds.com/ Diane's sells high quality seeds. Her selections are minimal but good.

www.seedsavers.org/Content.aspx?src=buyonline.htm A seed exchange and vault dedicated to preserving biodiversity.

http://nativeseeds.org/catalog/index.php?cPath=1 Specializing in seeds of the southwest desert and native cultures.

www.selectseeds.com/cgi-bin/htmlos.cgi/2010/catalog.htm Specializing in open pollinated annual flowers and other antique varietals.

www.victoryseeds.com/ Rare, Open-pollinated & Heirloom Garden Seeds

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

Annuals Heart Heat . . . by guest blogger Jeanette Ankoma-Sey

Annuals are annuals for a reason, but there are those that can take the abuse of heat and neglect and still not break a sweat. These three are a few I like to add here and there to add some sauciness to the landscape. These overlooked plants have such great qualities for those hot as Hades garden environs where many other plants can succomb to the heat and humidity.

First is Tithonia rotundifolia, Butterfly Torch, or sometimes called, Mexican Sunflower. If this flame can grow in the heat South of the Border it also shows itself to be a thrive-er in the glory of our D.C. metropolitan area summers. Looking similar to an overgrown version of the traditional marigold, this plant has beautiful soft green foliage and daisy orange-red flowers. Standing up to as tall as 6’ in height, Tithonia looks great in the middle to back of the planting bed and amongst perennials and other annuals, such as the previously mentioned Centaurea cyanus, blue and orange dreamy hues! The hotter and more miserable the climate, the happier and cherrier Tithonia is. Also, with ‘butterfly’ in the name this is a habitat winner and is a gracious host and an attractor of butterflies, Monarch and Swallotails to boot!! With its vibrant hues in the garden you cannot help but call out an ‘Ole!’ when you see Tithonia.

Next up is Ricinus communis, known as a Castor plant. Now this plant does summon all things questionable and is a poisonous plant, so it is best located far removed from direct interaction. The green, red/maroon/violet, massive palmate leaves tower over many other plants, and people, in the summer. This brings forth the lush tropical feel to any garden or container. The leaves even make a lovely cut plant for indoor arrangements. Pair it with blues, purples or deeper reds for a very mysterious yet mesmerizing combination. The flowers do not do much for me personally but the fruit seed heads are lovely little spikey orb clusters. Just one single plant can make a statement in a garden leaving people wondering always, ‘What’s that plant!?’ But why stop at one?

Last, a favorite that brings forth (plant) emotion always is Amaranthus caudatus, Love Lies Bleeding. If that name doesn’t send shivers down your spine then I don’t know what would! The drooping red spires of flowerlets make a big , heart-felt, romantic statement. If Snuffaluffagus were a flower, this would be the one! A trooper for all unkind conditions, LLB is a beauty in the garden and makes a great cut flower option too! There are orange, yellow and even chartreuse versions of the same plant and braid like flowers. Oh so delightful.

Jeanette Ankoma-Sey is a D.C. based landscape architect and a planting designer extraordinaire. She specializes in landscapes that provide sustenance, children's gardens, and school and botanical gardens. She teaches planting design at the George Washington University's Landscape Design Program.

First is Tithonia rotundifolia, Butterfly Torch, or sometimes called, Mexican Sunflower. If this flame can grow in the heat South of the Border it also shows itself to be a thrive-er in the glory of our D.C. metropolitan area summers. Looking similar to an overgrown version of the traditional marigold, this plant has beautiful soft green foliage and daisy orange-red flowers. Standing up to as tall as 6’ in height, Tithonia looks great in the middle to back of the planting bed and amongst perennials and other annuals, such as the previously mentioned Centaurea cyanus, blue and orange dreamy hues! The hotter and more miserable the climate, the happier and cherrier Tithonia is. Also, with ‘butterfly’ in the name this is a habitat winner and is a gracious host and an attractor of butterflies, Monarch and Swallotails to boot!! With its vibrant hues in the garden you cannot help but call out an ‘Ole!’ when you see Tithonia.

Next up is Ricinus communis, known as a Castor plant. Now this plant does summon all things questionable and is a poisonous plant, so it is best located far removed from direct interaction. The green, red/maroon/violet, massive palmate leaves tower over many other plants, and people, in the summer. This brings forth the lush tropical feel to any garden or container. The leaves even make a lovely cut plant for indoor arrangements. Pair it with blues, purples or deeper reds for a very mysterious yet mesmerizing combination. The flowers do not do much for me personally but the fruit seed heads are lovely little spikey orb clusters. Just one single plant can make a statement in a garden leaving people wondering always, ‘What’s that plant!?’ But why stop at one?

Last, a favorite that brings forth (plant) emotion always is Amaranthus caudatus, Love Lies Bleeding. If that name doesn’t send shivers down your spine then I don’t know what would! The drooping red spires of flowerlets make a big , heart-felt, romantic statement. If Snuffaluffagus were a flower, this would be the one! A trooper for all unkind conditions, LLB is a beauty in the garden and makes a great cut flower option too! There are orange, yellow and even chartreuse versions of the same plant and braid like flowers. Oh so delightful.

Jeanette Ankoma-Sey is a D.C. based landscape architect and a planting designer extraordinaire. She specializes in landscapes that provide sustenance, children's gardens, and school and botanical gardens. She teaches planting design at the George Washington University's Landscape Design Program.

Monday, April 12, 2010

How a Frenchman became America's Hottest Landscape Architect: A Focus on Michel Desvigne

Michel Desvigne is having his American moment. One of the most celebrated French landscape architects has recently completed a spate of high profile American commissions.

Desvigne’s recent U.S. work includes the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (with architects Herzog & de Meuron), the Dallas Center for the Performing Arts (with architects Norman Foster and REX/OMA), and the St. Louis Art Museum (with architect David Chipperfield).

Desvigne owes much of his recent success to his association with European starchitects such as Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Herzog and de Meuron, and Jean Nouvel. Cities across the globe are turning to these celebrity architects to revive neglected urban areas by creating sensational cultural buildings. When cities want an architectural adrenaline shot—what Gehry did for Bilbao, Spain—then Desvigne is often the corresponding landscape architect.

The irony is that Desvigne’s designs are anything but iconic. “Having reached what one architecture critic described as the midpoint in my career, I feel I have nothing to show,” describes Desvigne in the introduction to his book Intermediate Natures: The Landscapes of Michel Desvigne. He continues, “Or at least nothing that resembles the seductive images in architecture books.”

Perhaps it is precisely because Desvigne’s work resists formal composition and design stylization that makes him so compatible with celebrity architects. His landscapes are a field to their objects, a living fabric that knits together the architectural pieces. In Dallas, Desvigne’s ten acre Sammons Park offers a green foil to the complex of opera houses, theaters, and ampitheaters that sprawl over the loosely defined district. The park is rather minimal in its design and detail. Blocks of lawn combine with strips of concrete, and the young trees and “micro-gardens” give the landscape an in-the-works feeling.

Perhaps it is precisely because Desvigne’s work resists formal composition and design stylization that makes him so compatible with celebrity architects. His landscapes are a field to their objects, a living fabric that knits together the architectural pieces. In Dallas, Desvigne’s ten acre Sammons Park offers a green foil to the complex of opera houses, theaters, and ampitheaters that sprawl over the loosely defined district. The park is rather minimal in its design and detail. Blocks of lawn combine with strips of concrete, and the young trees and “micro-gardens” give the landscape an in-the-works feeling.

Desvigne’s recent U.S. work includes the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (with architects Herzog & de Meuron), the Dallas Center for the Performing Arts (with architects Norman Foster and REX/OMA), and the St. Louis Art Museum (with architect David Chipperfield).

Desvigne owes much of his recent success to his association with European starchitects such as Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Herzog and de Meuron, and Jean Nouvel. Cities across the globe are turning to these celebrity architects to revive neglected urban areas by creating sensational cultural buildings. When cities want an architectural adrenaline shot—what Gehry did for Bilbao, Spain—then Desvigne is often the corresponding landscape architect.

The irony is that Desvigne’s designs are anything but iconic. “Having reached what one architecture critic described as the midpoint in my career, I feel I have nothing to show,” describes Desvigne in the introduction to his book Intermediate Natures: The Landscapes of Michel Desvigne. He continues, “Or at least nothing that resembles the seductive images in architecture books.”

Perhaps it is precisely because Desvigne’s work resists formal composition and design stylization that makes him so compatible with celebrity architects. His landscapes are a field to their objects, a living fabric that knits together the architectural pieces. In Dallas, Desvigne’s ten acre Sammons Park offers a green foil to the complex of opera houses, theaters, and ampitheaters that sprawl over the loosely defined district. The park is rather minimal in its design and detail. Blocks of lawn combine with strips of concrete, and the young trees and “micro-gardens” give the landscape an in-the-works feeling.

Perhaps it is precisely because Desvigne’s work resists formal composition and design stylization that makes him so compatible with celebrity architects. His landscapes are a field to their objects, a living fabric that knits together the architectural pieces. In Dallas, Desvigne’s ten acre Sammons Park offers a green foil to the complex of opera houses, theaters, and ampitheaters that sprawl over the loosely defined district. The park is rather minimal in its design and detail. Blocks of lawn combine with strips of concrete, and the young trees and “micro-gardens” give the landscape an in-the-works feeling. “He has a fascination with the unfinished,” says American landscape architect James Corner. “He does not seem at all bothered that a landscape architectural project may appear raw, young, still-in-development.” Corner and Desvigne are transatlantic intellectual allies. Both landscape architects share similar conceptual approaches that eschew form-making and embrace agriculture as a metaphor for urban intervention.

Perhaps Desvigne’s interest in agricultural landscapes is the key to understanding his work. Agricultural sites differ from scenic landscapes in the fact that they are working and ever-changing landscapes. In the agricultural setting, people work the land and dwell in it, a pragmatic model Desvigne considers appropriate for urban sites. The landscape is not a static object to be looked upon, but a field in which we dwell. “I like poplar groves, orchards, artificially planted forests,” describes Desvigne, “I like to perceive these spaces whose conventional order is forgotten so that they are only densities, variations on density. Neither full nor empty, these squared spaces are sieves of a sort, where paradoxically life moves in—traps for an intermediate nature.” (Image below Keio University, Tokyo).

The influence of agriculture—or more broadly geography—is seen more literally in his design for the Millennium Park in London. The site was a former gasworks that required radical decontamination efforts that leveled the site and created a tabula rasa. Desvigne rejected the idea of creating a large urban park with predictable lawns, playgrounds, and natural areas. Instead, he advocated for the creation of an “intermediate landscape” to give texture and density to the formless site. Inspired by images of aerial photos of alluvial forests, Desvigne called for more than twelve thousand native hornbeam trees and over one hundred thousand shrubs to be densely planted in a grid with clearings indicated for future park activities. The design created a flexible framework for future development that considered the park’s evolution through time.

This process based approach is a hallmark of Desvigne’s work. It gives his work a quality of anticipation and possibility. “I think it is important to hold out against clichés, to play with the multitude, with the successions,” writes Desvigne, “There is no ‘beautiful’ image, nor should there be, except by accident.”

Saturday, April 10, 2010

The Ugly Corner of Sod: Lessons from my First Garden

My first garden was a small corner of my parent’s backyard, the only flat piece of an otherwise sharply sloping back lawn. I was in the fourth grade, and one morning I woke with the idea to grow tomatoes. I shuffled through the garage and emerged with a shovel and pickaxe. I marked out a rectangle and then hacked and sacked through the sod and clay. The first tomatoes came months later, a slim crop of Better Boys and Early Girls.

I remember two things from that day. First, I vividly recall the raw power and effort it took to break into that ground. Each time I raised that pickaxe above my head, I pretended to be Pharaoh’s slave, or a prisoner on a chain gang. It was an immense effort that demanded back and hamstring, shoulder and wrist.

The second thing I remember was a feeling of deep satisfaction. At the end of that day, I felt like Jacob after successfully wrestling an angel for a blessing. Gardeners universally know this feeling. It’s not just the satisfaction of completing a job, but it is the feeling of connecting with a particular piece of earth.

To garden is to enter a relationship with a piece of ground. At its essence, all of our digging, weeding, tilling, and planting are not about control, but about knowing. Not about improving, but about listening. The human impulse to mark the earth with lines—a row of crops, the setting of a foundation, a hedgerow on the horizon—is primal and necessary. We strike the earth in order to live. We draw, dig, pull, push, cut, and stack lines upon the landscape. These lines connect us and our human activity to the earth. They are our roots.

I have long been an advocate for sustainable and natural gardening, but I above all, I am an advocate for gardening. If the act of gardening is a relationship, then low maintenance gardening is code for “let’s just be friends.” Or “I’m just not that into you.” Though I make my living designing gardens, I’d rather see one ugly, but beloved amateur garden than a hundred transcendent designer gardens with an owner who doesn’t care. They are like museums without visitors.

This year I’m not growing tomatoes. I have too little space and too many other plant infatuations. But I am digging and transplanting, weeding and mulching. Because it is not so much what I do, than the fact that I do. On a balmy day in April, I sink my hands into soil that has been warmed by the sun. It is loose and dark from years of gardening. I stand up and look across the overcrowded garden. And I wish for an ugly corner of sod to wrestle with.

I remember two things from that day. First, I vividly recall the raw power and effort it took to break into that ground. Each time I raised that pickaxe above my head, I pretended to be Pharaoh’s slave, or a prisoner on a chain gang. It was an immense effort that demanded back and hamstring, shoulder and wrist.

The second thing I remember was a feeling of deep satisfaction. At the end of that day, I felt like Jacob after successfully wrestling an angel for a blessing. Gardeners universally know this feeling. It’s not just the satisfaction of completing a job, but it is the feeling of connecting with a particular piece of earth.

To garden is to enter a relationship with a piece of ground. At its essence, all of our digging, weeding, tilling, and planting are not about control, but about knowing. Not about improving, but about listening. The human impulse to mark the earth with lines—a row of crops, the setting of a foundation, a hedgerow on the horizon—is primal and necessary. We strike the earth in order to live. We draw, dig, pull, push, cut, and stack lines upon the landscape. These lines connect us and our human activity to the earth. They are our roots.

I have long been an advocate for sustainable and natural gardening, but I above all, I am an advocate for gardening. If the act of gardening is a relationship, then low maintenance gardening is code for “let’s just be friends.” Or “I’m just not that into you.” Though I make my living designing gardens, I’d rather see one ugly, but beloved amateur garden than a hundred transcendent designer gardens with an owner who doesn’t care. They are like museums without visitors.

This year I’m not growing tomatoes. I have too little space and too many other plant infatuations. But I am digging and transplanting, weeding and mulching. Because it is not so much what I do, than the fact that I do. On a balmy day in April, I sink my hands into soil that has been warmed by the sun. It is loose and dark from years of gardening. I stand up and look across the overcrowded garden. And I wish for an ugly corner of sod to wrestle with.

Thursday, April 8, 2010

Confessions of an Annual Snob: Seven Killer Annuals Even I Love

My confession: I was an annual snob. For years I was too good for them. Leave those overly happy, Home Depot specials for the non-gardeners. Real gardeners use perennials or grasses.

But this year, I am softening. My recent interest in propagating my own plants has led me to discover a new side to those short-lived, ever-blooming plants. Perennials can be tough to start from seed, but annuals are easy. After many half-successes with perennials, I was ready for something that didn’t require six weeks of cold stratification in my refrigerator, or wait two seasons to bloom. Browsing seed catalogues, I discovered a handful of annuals—many of them heirlooms—that mix beautifully with the perennial border.

Perennial gardeners know how hard it is to get a really intense spectacle out of perennials. They bloom for such a short time. Consider adding a few of these annuals to jazz up your permanent garden.

Annuals to Interplant with Perennials and Grasses:

1. Zinnia Benary Giant Series, Zinnia: These are not your grandmother’s Zinnias. This new line of Zinnias have some of the highest quality blooms of any Zinnias I’ve seen. They seem to handle the heat better than other varieties I’ve used. The best part is the range of colors. This year, I’m mixing ‘Benary Giant Wine’ with Lavander and pink roses. ‘Giant Lime’ is another great pick that could mix well with your blue and purple perennials. The blooms are massive.

2. Emilia javanica, Lady’s Paint Brush: If you’re into the natural look like me, this plant will steal your heart. Tiny fire-colored blooms top the ends of long, grassy stems. This plant could mix well almost any low grass (Pennisetum, Sesleria, Schizachyrium, Nasella) or perennial. This year, I’m mixing it with Nasella tenuissima for a fiery effect.

3. Verbena bonariensis, Vervain: Pick up any garden magazine in the last year, and you’re almost sure to see this Verbena in it. Purple flower bunches sit on top of leggy stems, making a great plant to mix in between already established plants. Butterflies love it, and the color mixes with almost anything. Use in the middle or back of your border, as it can get up to four feet tall. If you’re lucky, it may reseed.

4. Papaver rupifragum ‘Double Tangerine Gem’, Tangerine Poppy: Did I say annual? Ok, so I’m throwing one perennial in this mix because it can be grown from seed so easily and sets flower the first year. The color on this hardy poppy is unbelievable. If you’re one of those gardeners who is hesitant about using the color orange, then this is your gateway plant to tangerine nirvana. Mix in the front of the border with grasses, salvias, or nepetas.

5. Centaurea cyanus, Cornflower: You’ve probably seen this ubiquitous wildflower happily blooming on the side of the road. It’s the quintessential annual meadow flower. Despite its ubiquity, it is rarely used in gardens. It is one of the easiest flowers to grow from seed, and mixes with almost anything. Great for the natural garden. This year, I’m mixing Centaurea ‘Black Ball’ with Briza media. Because black is the new black.

Two Annuals to that Will Carry Your Perennial Border

6. Salvia leucantha, Mexican Sage Bush: If you live in Southern California, Mexican Sage Bush is a work horse perennial. But for gardeners north of Zone 8, this annual will make your border. Growing 24-48” tall and wide, this salvia blooms all summer long. Pollinators love it.

7. Leonotis leonurus, Wild Dagga: Walking through the U.S. Botanical Garden last October, I was blown away by this spectacular plant. Growing four to five feet tall and wide, this South African annual was literally covered in orange monarda-like blooms. Pollinators really go crazy for this member of the Lamiaceae family. The plant is sold on the internet as a marijuana alternative (smoking the flowers creates a feeling of euphoria), but the flowers are intoxicating enough for me. Combine with Salvia leucantha for a truly spectacular early autumn display.

But this year, I am softening. My recent interest in propagating my own plants has led me to discover a new side to those short-lived, ever-blooming plants. Perennials can be tough to start from seed, but annuals are easy. After many half-successes with perennials, I was ready for something that didn’t require six weeks of cold stratification in my refrigerator, or wait two seasons to bloom. Browsing seed catalogues, I discovered a handful of annuals—many of them heirlooms—that mix beautifully with the perennial border.

Perennial gardeners know how hard it is to get a really intense spectacle out of perennials. They bloom for such a short time. Consider adding a few of these annuals to jazz up your permanent garden.

Annuals to Interplant with Perennials and Grasses:

1. Zinnia Benary Giant Series, Zinnia: These are not your grandmother’s Zinnias. This new line of Zinnias have some of the highest quality blooms of any Zinnias I’ve seen. They seem to handle the heat better than other varieties I’ve used. The best part is the range of colors. This year, I’m mixing ‘Benary Giant Wine’ with Lavander and pink roses. ‘Giant Lime’ is another great pick that could mix well with your blue and purple perennials. The blooms are massive.

2. Emilia javanica, Lady’s Paint Brush: If you’re into the natural look like me, this plant will steal your heart. Tiny fire-colored blooms top the ends of long, grassy stems. This plant could mix well almost any low grass (Pennisetum, Sesleria, Schizachyrium, Nasella) or perennial. This year, I’m mixing it with Nasella tenuissima for a fiery effect.

3. Verbena bonariensis, Vervain: Pick up any garden magazine in the last year, and you’re almost sure to see this Verbena in it. Purple flower bunches sit on top of leggy stems, making a great plant to mix in between already established plants. Butterflies love it, and the color mixes with almost anything. Use in the middle or back of your border, as it can get up to four feet tall. If you’re lucky, it may reseed.

4. Papaver rupifragum ‘Double Tangerine Gem’, Tangerine Poppy: Did I say annual? Ok, so I’m throwing one perennial in this mix because it can be grown from seed so easily and sets flower the first year. The color on this hardy poppy is unbelievable. If you’re one of those gardeners who is hesitant about using the color orange, then this is your gateway plant to tangerine nirvana. Mix in the front of the border with grasses, salvias, or nepetas.

5. Centaurea cyanus, Cornflower: You’ve probably seen this ubiquitous wildflower happily blooming on the side of the road. It’s the quintessential annual meadow flower. Despite its ubiquity, it is rarely used in gardens. It is one of the easiest flowers to grow from seed, and mixes with almost anything. Great for the natural garden. This year, I’m mixing Centaurea ‘Black Ball’ with Briza media. Because black is the new black.

Two Annuals to that Will Carry Your Perennial Border

6. Salvia leucantha, Mexican Sage Bush: If you live in Southern California, Mexican Sage Bush is a work horse perennial. But for gardeners north of Zone 8, this annual will make your border. Growing 24-48” tall and wide, this salvia blooms all summer long. Pollinators love it.

7. Leonotis leonurus, Wild Dagga: Walking through the U.S. Botanical Garden last October, I was blown away by this spectacular plant. Growing four to five feet tall and wide, this South African annual was literally covered in orange monarda-like blooms. Pollinators really go crazy for this member of the Lamiaceae family. The plant is sold on the internet as a marijuana alternative (smoking the flowers creates a feeling of euphoria), but the flowers are intoxicating enough for me. Combine with Salvia leucantha for a truly spectacular early autumn display.

Wednesday, April 7, 2010

The Wild Garden

What in your garden is truly wild?

At its heart, the sustainable gardening movement is about creating gardens that look and act more like nature. Or at least an interpreted form of it. But how many of our gardens actually let wildness in? Do we allow plants to self-seed and roam freely? Are happy accidents permitted, or do we quickly correct them and steer the garden back on course?

The concept of wildness in gardens is not new. But the topic is hotter than ever these days. Author, lecturer, photographer, and designer Rick Darke has recently revived William Robinson's classic tome The Wild Garden. William Robinson (1838-1935) introduced a revolutionary book in 1870 that advocated an authentically natural approach to planting design. Now Rick Darke has republished this timeless work, complete with Darke's own photographs and preface.

No one in America has Rick Darke’s eye for plants in their natural habitat. Darke is one of the few planting photographers today to get beyond the horticultural close up and show plants living and growing in their natural habitats. The result is dramatic. Darke’s books are literally changing planting design in America, as his photographs serve as powerful inspiration to landscape architects and gardeners. Now those photographs come together with Robinson’s timeless text.

The Idea of Wildness

The concept of wilderness has inspired literature throughout the centuries. But Robinson dispenses with this mythic “wilderness” and offers a concept of wildness that is entirely relevant for creating a modern, ecological landscape ethic. The wild garden, “has nothing to do with the old idea of ‘Wilderness,’” writes Robinson in his preface. Robinson’s wild garden is not a pristine sanctuary untouched by human hands, but a place where human activity and natural ecology intersect. “Some have thought of it as a garden run wild,” Robinson says.

A New Aesthetic

That Robinson’s wild garden does not preclude human intervention, but welcomes it, makes it the starting point for any gardener serious about sustainable design. Chapter by chapter, Robinson richly describes strategies for arranging plants to work within naturally occurring plant communities. Robinson is a plantsman’s plantsman. Each chapter focuses on solid techniques for combining plants into various natural habitats, creating a hybrid space that is at once wild and man-made.

His combinations are poetic: double crimson peonies dotted through a field of native grasses; clumps of yellow alliums growing along a forgotten fenceline; or drifts of Lily of the Valley gathered in a sunny copse in the woods. His work describes a new aesthetic: a third nature where cherished cultivated plants intermingle freely with effervescent native vegetation.

In addition to the text, the book has almost a hundred exquisite drawings and engravings by British artist Alfred Parsons. The drawings bring to life Robinson’s vision, adding a moody richness that conceals as much as it reveals.

The Wild Garden is essential reading for any plant designer, landscape architect, or gardener. This textbook provides layers of inspiration and depth not offered by today’s coffee table books on planting. Since reading this book, my planting designs have been liberated, and I owe a debt to Robinson and Darke for expanding my imagination.

At its heart, the sustainable gardening movement is about creating gardens that look and act more like nature. Or at least an interpreted form of it. But how many of our gardens actually let wildness in? Do we allow plants to self-seed and roam freely? Are happy accidents permitted, or do we quickly correct them and steer the garden back on course?

The concept of wildness in gardens is not new. But the topic is hotter than ever these days. Author, lecturer, photographer, and designer Rick Darke has recently revived William Robinson's classic tome The Wild Garden. William Robinson (1838-1935) introduced a revolutionary book in 1870 that advocated an authentically natural approach to planting design. Now Rick Darke has republished this timeless work, complete with Darke's own photographs and preface.

No one in America has Rick Darke’s eye for plants in their natural habitat. Darke is one of the few planting photographers today to get beyond the horticultural close up and show plants living and growing in their natural habitats. The result is dramatic. Darke’s books are literally changing planting design in America, as his photographs serve as powerful inspiration to landscape architects and gardeners. Now those photographs come together with Robinson’s timeless text.

The Idea of Wildness

The concept of wilderness has inspired literature throughout the centuries. But Robinson dispenses with this mythic “wilderness” and offers a concept of wildness that is entirely relevant for creating a modern, ecological landscape ethic. The wild garden, “has nothing to do with the old idea of ‘Wilderness,’” writes Robinson in his preface. Robinson’s wild garden is not a pristine sanctuary untouched by human hands, but a place where human activity and natural ecology intersect. “Some have thought of it as a garden run wild,” Robinson says.

A New Aesthetic

That Robinson’s wild garden does not preclude human intervention, but welcomes it, makes it the starting point for any gardener serious about sustainable design. Chapter by chapter, Robinson richly describes strategies for arranging plants to work within naturally occurring plant communities. Robinson is a plantsman’s plantsman. Each chapter focuses on solid techniques for combining plants into various natural habitats, creating a hybrid space that is at once wild and man-made.

His combinations are poetic: double crimson peonies dotted through a field of native grasses; clumps of yellow alliums growing along a forgotten fenceline; or drifts of Lily of the Valley gathered in a sunny copse in the woods. His work describes a new aesthetic: a third nature where cherished cultivated plants intermingle freely with effervescent native vegetation.

In addition to the text, the book has almost a hundred exquisite drawings and engravings by British artist Alfred Parsons. The drawings bring to life Robinson’s vision, adding a moody richness that conceals as much as it reveals.

The Wild Garden is essential reading for any plant designer, landscape architect, or gardener. This textbook provides layers of inspiration and depth not offered by today’s coffee table books on planting. Since reading this book, my planting designs have been liberated, and I owe a debt to Robinson and Darke for expanding my imagination.

Tuesday, April 6, 2010

Secrets of the Highline Revealed!